Blessy on Aadujeevitham’s spiritual aspects: Elements like Ibrahim Khadiri sacrificing gave the film another dimension

1 month ago | 5 Views

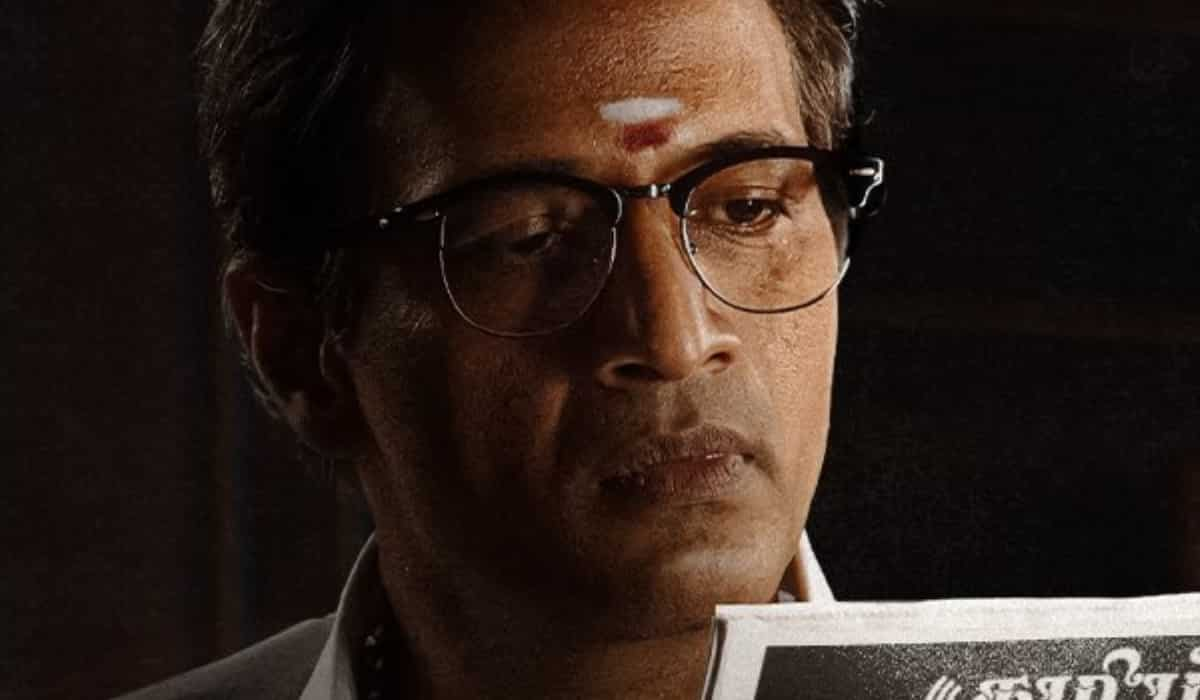

Most assistant directors in the Malayalam film industry are often quoted with the example of filmmaker Blessy, when they have had to wait for years to make their debut. Taking time – sometimes even decades – to make a project isn’t something new for Blessy, whose latest movie Aadujeevitham took about 16 years to hit theatres since he had first bought the rights from its author Benyamin in 2008. The wait, was well worth it, as signified by the box office collection as well as the critical acclaim the Prithviraj Sukumaran-starrer has earned over the past few days.

In a candid interview with OTTplay, Blessy talks about the spiritual aspects of the movie and how it drove to make the film, his fascination for subjects with intangible elements and emotions, and if Aadujeevitham’s theatrical version still felt incomplete.

Aadujeevitham is a story of Najeeb’s survival and resilience. Having been attached to the film from 2008, what was it that sustained your drive to stick with the film through the thick and thin?

It’s not an experience that I have got just by doing this one film. After I began my career as an assistant director in 1986, it took me 18 years to helm my first film. That’s a long wait. The journey had disappointments, failures, sorrow and happiness; it had phases where my youth was lost without me not reaching anywhere in life. I directed my first film when I was in my 40s.

In the Bible, there’s a verse that says, ‘Blessed is he who waits.’ We find meaning in most of these through our life’s experiences. So, not everything has to happen fast. If I had done a film in 10 years instead of 18, I might not have been a writer. So, I attribute my being a writer to that wait. During that wait, it’s not that I am staring at the sky, expecting rain, like a Hornbill. I am working during that time and that work adds value.

There’s a sense of confidence that one gets when they are sure that they would be good at only this and not anything else. That should always stem from the work they do. That was the case for me.

The film also is a spiritual journey. How much did the faith aspect of Najeeb’s story appeal to you – that you wanted to give it a visual adaptation?

How do you believe in the concept that there’s a tomorrow? Is it through science or spirituality? Similarly, a lot of truths in the world are not something that can be seen through eyes, including the breath that sustains your life. What’s really immortal is the love and respect that a person feels for the other – and there’s visual form or body to these. So, how can a human being who is dependent on every breath that one takes say that they would wake up tomorrow? It’s faith.

Be it Kaazcha, Thanmathra or even Aadujeevitham, like you said, it’s driven by these intangible emotions and that’s not easy to do. Do you gravitate more towards such subjects?

I am most comfortable in Malayalam and so, I am able to express the most when I talk in Malayalam than in any other language and people are able to understand me the best. It’s solely because it’s become a practice for which I don’t have to pay too much attention. Similarly, when I do a film there are certain aspects or emotions that I have to include. I don’t know whether it’s good or bad, but I believe that’s what connects my films and characters to the audience. If they didn’t, the movie would fail. From my very first film, I have wished that the audience shouldn’t be able to leave my movie once they leave the theatres. They have to travel with that.

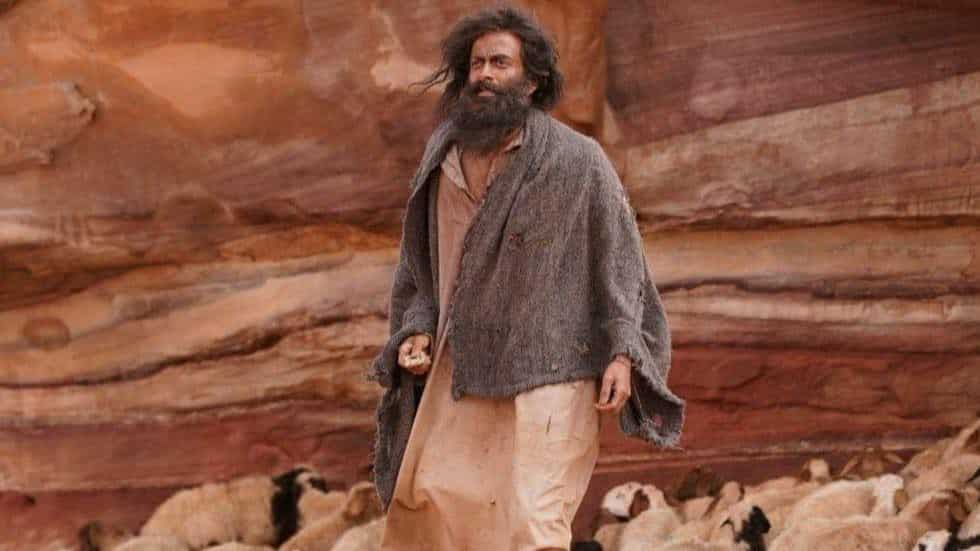

Those who connected the film as well as the book could do it either because it reminded them of the many immigrants who had gone abroad in search of greener pastures and had to face similar ordeals, or because it had a spiritual element – especially in the second half – where Najeeb, Hakeem and Ibrahim Khadiri set out for their escape. When you are making a film based on a popular novel that has deeply moved multitudes, how important was it to tell your interpretation of this story?

It was. The scene where Khadiri (played by Jimmy Jean Louis) tells Najeeb that ‘must walk till we die’ is not part of the book. The Somalian tearing his jacket and wrapping it around Najeeb’s feet or him giving his boots to him and walking barefoot aren’t part of the book either. All of this is done by a wanted criminal. There’s spirituality in a person, who is accused by others; a hint of virtue. Even though we don’t delve too much into that in the film, Ibrahim Khadiri, in essence, is sharing his body through his clothes and shoes. That a criminal is doing it, is what gives those sequences an entirely new dimension.

When you have put in so many years to work on this movie as well as shoot it, there would have been so many scenes that wouldn’t have made the theatrical cut? Did that give it a sense of incompleteness to the whole project?

We can’t say that. During every stage, we have only shot what we thought we wanted for the film. Aadujeevitham isn’t a usual type of film; it’s more like a one-act play. Audiences who aren’t used to watching such movies would find it tedious and some sequences unnecessary. We didn’t include the scene where they ran behind a truck and didn’t get to it. But that’s how editing it; we try to include the most relevant portions required to tell the story.

A common grouse among those who had watched was Najeeb’s relationship with the livestock in the masara, where he had spent years, wasn’t quite explored and this took away the emotional impact of the film.

The interpretations can be different for each person. In that shot where he finally looks back at the livestock just before escaping, there are people who might have liked the twinkling hope in his eyes and others who didn’t. Najeeb is actually going towards an even more horrible ordeal from the masara. That’s why we didn’t want to add more drama to that sequence.

Also, it wasn’t my responsibility to interpret the novel just like it is written. In the scene, he talks to the camels and sheep – underlining his relationship with them. All of this is because people have read the novel and have imagined how the scenes would have panned out. I was already aware of these challenges and I was clear about what I wanted to do. If I had tried to establish that emotional sequence, then it would have become slow for the viewers. My task was to focus on what Najeeb goes through after that.

Even though you had spent year working on the script and the film, Prithviraj had said that there were times where you had let him perform – even if it meant it was not the same way you had written the scene – and let your intuition decide if it would work or not.

It’s not a movie where the scenes are developed based on dialogues between two characters. So, there was an idea what Najeeb had to convey through the scene. He’s someone who hasn’t talked for years and so to communicate what he wanted; I didn’t want Prithviraj to even say the entire line. I don’t want an artiste to mimic what I tell him to; an actor should understand and imbibe his character and portray it with all emotions. He has to be the person who hasn't talked for the past three years, the one who has lost muscle and mass. So, it’s a freedom that I can give to the actor who has been through that character’s journey, and I believe that’s why I have got such great results for the film.

After travelling for years with such a film, how does it affect your next project?

I won’t be able to answer that right now because I gravitate towards another subject only when it troubles me a lot. I will start writing only when I get involved with the subject on a deeper level. Sometimes it might happen in the next second, and sometimes it might require me to wait years.